Cooking and cuisine are a vital feature of African American culture, and Tampa’s community has a tasty but largely unsung past that is worthy of celebration.

For much of the city’s history, Tampa’s African American population prepared and consumed meals at home and at community events. In both locations, the cuisine held fast to the traditional cooking of the South, which enslaved Africans were instrumental in creating—slow smoked barbecue pork; chicken slathered in sticky sauce; chitterlings prepared by being soaked in water, cleaned with lemon juice, and simmered slowly, eaten awash with vinegar and hot sauce; cornmeal-dusted fried fish atop a soft mound of grits; smoked mullet wrapped in yesterday’s newspaper; ever-bubbling pots of greens with fatback. The menu of African American Tampans was remarkably resilient, preserved in part by the celebration of “soul food” and Black pride, both of which flowered in the 1960s and 1970s.

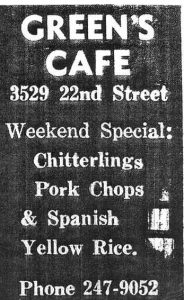

An advertisement for Green’s Cafe, located in Tampa, FL.

The specialties listed here only begin to tell the story, which–in Tampa–is a decidedly spicier history than either Jacksonville or Tallahassee. Thanks, in part, to Tampa’s Afro-Cuban community, Latin specialties became seamlessly incorporated into the foodways of Black Tampans. Such Cuban classics as arroz con pollo (chicken and yellow rice), Cuban sandwiches, and devil crab croquettes became favorites for many of Tampa’s Black residents. Cuban bread became as common as corn bread, and the steady flow of typical Florida produce, such as corn, beans, peas, greens, yams, strawberries and citrus, were supplemented with plantains, yucca, mango, and guava.

Much of Tampa’s African American community was deeply devoted to crab enchilado (also known as chilau and shelah) as a festive and collective dish. Made with whole blue crabs simmered in a spicy tomato sauce and served over spaghetti, enchilado was especially prized for being easily made with inexpensive ingredients after a day of catching crabs. By virtue of its flavor and frugality, the dish even supplanted pork as the centerpiece of many local tables. One vivid description of a family’s West Tampa crab and sauce ritual comes from an interview with Otis Anthony. Remembering the 1950s and 60s, Anthony recalled:

Great get-togethers in the backyard. We had huge buckets of ice, buckets of watermelon, and we would skin catfish with pliers, and we would have little knives to eat our sugarcane stalks with. Of course, the center meal for every get-together, believe it or not, it wasn’t pork. It was crab chilau (laughs) and if you had crab chilau, you know everybody on the block come by your house because they smell it cooking two miles down the road. It was blue crabs, none of this stuff we buy at Publix and Winn-Dixie today. (laughs) It’s a kind of Cuban-African-American way of doing this sauce. It’s highly seasoned with onions and garlic and bell pepper, and God knows what else. You slightly boil the crabs, then you cook them further in the crab chilau before you serve it, and it’s really good across a plate of spaghetti. And, of course, buttered Cuban bread. It was heaven!

When I grew up, on a Friday and Saturday night, up until four or five o’clock in the morning, we didn’t close the back door or the front door. We had screen doors and people flowed in and out and that was just a very natural way of living. And, if you wanted to come in and sit down, have a drink, have a laugh, and eat some crabs, you were welcome to whatever we had left in the pot. And it was that way with everybody in that neighborhood.

Racism gave rise to a local restaurant scene in which Black-owned eateries were marginalized by segregation, unequal opportunities for entrepreneurs, and a working-class clientele. The invisible color line meant that Black entrepreneurs had opportunities to cater to their communities but not beyond them. Racial exclusion also extended to the written record; most of Tampa’s community cookbooks were published by prominent White citizens. Guidebooks for White tourists never showcased Black businesses before integration, and rarely did afterward. Even guidebooks like the Negro Motorist Green-Book, provided scant information. For example, in 1938, it listed only 12 hotels and no restaurants in the entire state of Florida! Later guides listed Bruce’s, the Little Savoy nightclub, and Anthony’s Drive Inn as friendly dining options in Tampa.

Tampa’s Black neighborhoods teemed with food and frolics, especially on the weekends, when air became hazy with the smoke of wood-burning barbecue and the steam of simmering pots. Skillets and kettles of frying fish supplied neighborly parties and church picnics. Locals also enjoyed dining out, and the marketplace offered some enticing options.

At the turn of the century, several Black communities were scattered around Tampa, but the biggest concentration of Black-owned businesses was along a five-block stretch of Central Avenue. It was along this strip that an assortment of bars, clubs, groceries, drug stores and diners operated as a counterpart to downtown Tampa. In an interview, Ms. Watts Sanderson provided a virtual walk down Central Avenue, recalling all the black-owned businesses, which included several eateries and drinking establishments:

Saunders Central Blue Room Bar and Grill. We had right next door the Palm Dinette. A little bit further down the street we had Rogers Hotel and the Rogers Dining Room. We had the Cotton Club, that was also a bar. We had Johnny Gray’s restaurant that was next to the Lincoln. We had Kid Mason, and his slogan was ‘From Ice Cream to Hardware,’ and I want you to know that it fit. Then right around the corner we had Shelly Green Cafe. We had the Palace Drug Store.

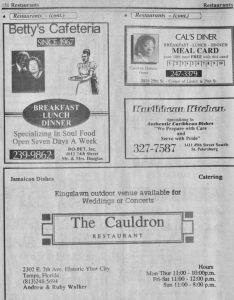

Restaurant ads published in the Tampa/St. Petersburg Metropolitan Black Pages, 1992.

Places like the Cozy Corner, Bexley’s Barbecue, Central Quik Lunch, Betty’s Cafeteria, Frank-El, and Big John’s Alabama Barbecue have all provided homes away from home to generations of African Americans in Tampa. Otis Anthony’s comments on Central Avenue’s social scene also apply to Black Tampa as a whole: “Central [Avenue] had all classes of Blacks talking together, dancing, laughing, arguing, and living what must have seemed to outside observers the happy life of a people who had much to be unhappy about.’

The USF Libraries Special Collections includes historical resources that document the culture and history of African American cuisine in Tampa, FL. Visit Special Collections in person or online to learn more about the materials referenced in this post and others, listed below.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Florida Civil Rights Oral History project, USF Libraries Digital Collections, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fl_civil_rights_ohp/

Florida restaurant menu collection, USF Libraries – Tampa Special Collections, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL. https://archives.lib.usf.edu/repositories/2/resources/337

USF Department of Anthropology African Americans in Florida Project, USF Libraries – Tampa Special Collections, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL. https://archives.lib.usf.edu/repositories/2/resources/480 Accessed August 29, 2023.

Credit: Andy Huse, Curator of Florida Studies, USF Libraries Tampa Special Collections