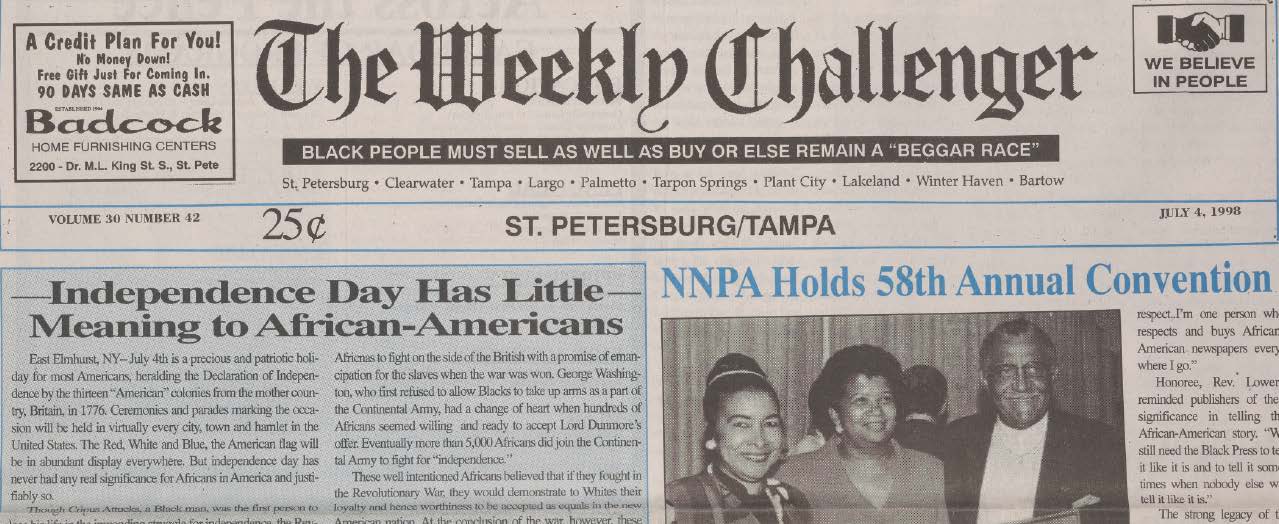

Readers of the July 4, 1998, edition of The Weekly Challenger were confronted with a bracing front-page headline: “Independence Day Has Little Meaning to African-Americans.” “July 4th is a precious and patriotic holiday for most Americans,” the piece begins, “heralding the Declaration of Independence by the thirteen ‘American’ colonies from the mother country, Britain, in 1776.”

Ceremonies and parades marking the occasion will be held in virtually every city, town and hamlet in the United States. The Red, White and Blue, the American flag will be in abundant display everywhere. But independence day has never had any real significance for Africans in America and justifiably so.

It goes on to note that though Black Americans took part in the struggle for independence from the Boston Massacre of 1770 on, they were not the intended beneficiaries of that struggle. Many of the most ardent revolutionaries, including Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry, were slaveowners, and Gen. George Washington agreed to let Blacks serve in the Continental Army only after the British offered emancipation to any slaves who joined Loyalist forces.

At the war’s end, of course, slavery remained legal in the new nation, and even free Blacks—including Revolutionary veterans—did not enjoy the full rights of citizenship. As the enslaved population grew and the institution expanded westward, the tensions between the sentiments of the Declaration of Independence and the realities of life in the United States became difficult to ignore. The piece invokes Frederick Douglass’s oration of July 4, 1852, in which he asked, “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?”

I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.

The Challenger piece concludes by noting the lynching of James Byrd Jr. that had occurred in Texas just a month earlier, a grim reminder of ongoing racial injustice, and suggests that Black Americans should celebrate the Fourth as a family holiday rather than a political event. But it does affirm the Declaration’s assertion that the oppressed have a “duty” to rebel against their oppressors.

Credit: Matt Barganier, Collections Specialist for Oral History